With its roots in 19th-century Texas, Juneteenth has grown into a popular event across the country to commemorate emancipation from slavery and celebrate African American culture. Juneteenth refers to June 19, the date in 1865 when the Union Army arrived in Galveston and announced that the Civil War was over and that slaves were free under the Emancipation Proclamation. Although the proclamation had become official more than two years earlier on January 1, 1863, freedmen in Texas adopted June 19th, later known colloquially as Juneteenth, as the date they celebrated emancipation. Juneteenth celebrations continued into the 20th century, and survived a period of declining participation because of the Great Depression and World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s Juneteenth celebrations witnessed a revival as they became catalysts for publicizing civil rights issues of the day. In 1980 the Texas state legislature established June 19 as a state holiday.

It wasn’t until the 1990s, however, that Juneteenth spread to other parts of the country, including Virginia. Inspired by a Juneteenth event at the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Community Museum in 1992, Juneteenth celebrations were being held each year in cities and towns throughout Virginia by the end of that decade. In a 2007 resolution, the Virginia House of Delegates recognized June 19 as “Juneteenth Freedom Day” in the state. Across the country, Juneteenth events now can range from small church affairs to grand celebrations that encompass a wide variety of activities, such as public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, speeches, parades, music, prayer services, and street fairs.

While Juneteenth has garnered recent popularity nationally, emancipation day celebrations traditionally have varied by locality and occurred on those dates in which slaves believed they were free from bondage. In Washington, D.C., emancipation is remembered on April 16, coinciding with that date in 1862 when Lincoln signed the Compensated Emancipation Act, which ended slavery in the nation’s capital. Known as Emancipation Day, April 16 became a public holiday in Washington, D.C., in 2005. In Norfolk the Union army gained control in May 1862, meaning that slaves there could feel free on January 1, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. Indeed, for most New Year’s Day has historically been the customary date to observe emancipation. In 1963 the United States Congress designated January 1 as Emancipation Proclamation Day. Many observe January 1 in conjunction with Watch Night, a traditional African American religious gathering that dates back to December 31, 1862, when abolitionists met to await word that the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued.

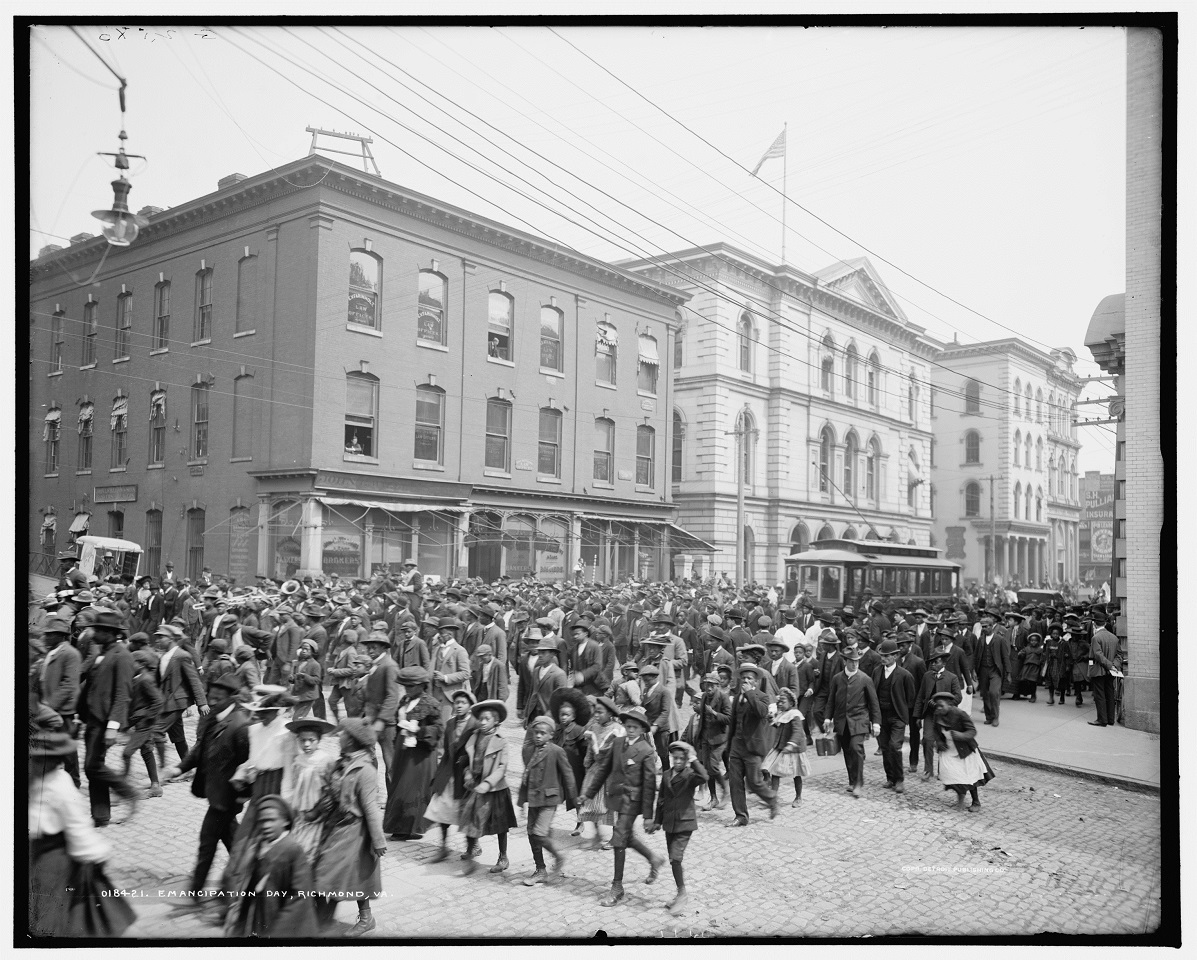

In the years following the Civil War, emancipation day celebrations in Richmond often took place on April 3, the date Union forces entered the city. Drawing hundreds and sometimes thousands of participants, these celebrations included public recitations of the Emancipation Proclamation, parades that ended at Capitol Square, music, prayer services, and speeches highlighting civic rights and voter registration. Illustrating the very personal experience of why this specific date was important to so many, the Richmond Planet quoted a local leader in 1890 who favored celebrating emancipation on “April 3d when Richmond fell, because that was the day that I shook hands with the Yankees.” These strong emotions were countered by equally strong passions from many white residents, angered that former slaves would publicly mark slavery’s end on April 3, which was known by the white population as Evacuation Day. Hostility exploded in 1866 when whites burned down a church being used for

emancipation day planning meetings and as a school for freedmen—another transformation anathema to many whites. To ameliorate these tensions, black leaders posted broadsides assuring whites that they did not wish to celebrate the collapse of the Confederacy but sought only to commemorate emancipation.

Another incendiary date also served to illustrate contrasting perceptions of blacks and whites in post–Civil War Virginia. In Richmond and even in smaller towns like Emporia, Clifton Forge, and Boydton, African Americans celebrated freedom from slavery on April 9, when Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered his forces to Union general Ulysses S. Grant. A less controversial date for emancipation day gatherings has been September 22, the date in 1862 when Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation. Spurring events in the 1890s in Loudoun and in Warrenton, among many other locales, this date remains popular for celebrating emancipation throughout the United States into the 21st century.

The decision as to when emancipation should be commemorated has fostered many debates dating back to the 19th century. Seeking to answer that question by establishing a self-defined “National Thanksgiving Day for Freedom,” Richmond African Americans sponsored a Colored People’s Celebration to be held during three days in October 1890. Broadsides advertised prominent speakers, including Virginia governor Philip Watkins McKinney, Richmond mayor James Taylor Ellyson, and John Mercer Langston, who recently had been seated in the United States House of Representatives as Virginia’s first African American congressman. The gala also included a parade, fireworks, and attractions at the exposition grounds. The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad even advertised special rates to promote attendance.

Emancipation day celebrations in Virginia and across the country can be traced to those dates and places when most African Americans personally experienced freedom for the first time. Regardless of when and where these observances took place, emancipation day commemorations also served as a public demonstration that the world had profoundly changed. Emancipation day celebrations are just one example, however, of the many arenas in which black and white citizens confronted one another in the new world of post–Civil War Virginia. For additional context and materials on Emancipation Day, please see our Shaping the Constitution resources.

An upcoming exhibition at the Library of Virginia, Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation, will explore how the end of the Civil War and emancipation affected Virginians, forcing those previously held in slavery and those who kept them in a state of bondage to renegotiate and transform their relationships. Using personal stories from the archival and manuscript collections at the Library, the project will focus on how African Americans made the change from property to citizens and will explore the societal transformation experienced by all Virginians through labor, church, education, families, political rights, military service, and violence. Remaking Virginia will be on view at the Library of Virginia from July 6, 2015 through March 26, 2016.

Thanks so much for sharing this as many still aren’t aware of what Juneteenth is and its importance.